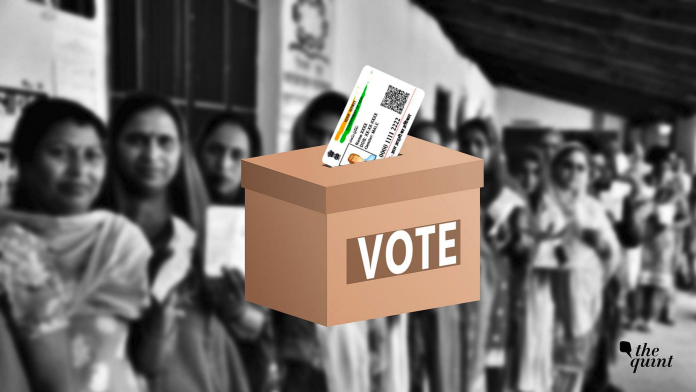

By including Aadhaar-voter ID linking in the Election Laws (Amendment) Bill 2021, the Centre opened up what would have otherwise been an extremely welcome piece of legislation to strong criticism.

Of course, that criticism has not affected the central government’s ability to force the legislation through Parliament. On Tuesday, 21 December, the bill was passed in the Rajya Sabha by voice vote, having been passed in the Lok Sabha without discussion the previous day.

It is perhaps understandable that for many people now there is an element of fatigue when it comes to criticisms of the government’s policy to link anything and everything to Aadhaar.

Despite the concerns of privacy experts, despite even a judgment of the Supreme Court, the Modi government has been relentless in widening a programme the prime minister himself called a ‘gimmick’ before 2014.

That it was going to be linked to the electoral rolls has seemed inevitable for quite some time (a pilot project for this had even been launched in 2015), and so it may therefore be tempting to just accept the government’s move without getting worked up about it.

This is not some hypothetical concern. The very purpose stated for the move is to clean up India’s electoral rolls, to deal with, as the bill’s Statement of Objects and Reasons says, “the menace of multiple enrolments.”

The problem is that even if conducted with the very best of intentions, making Aadhaar the instrument of this ‘purification’ exercise creates an added risk of exclusion. Not to mention the fact that instead of the election officials who have built a great deal of trust being responsible for this process, it now involves an outside authority with little accountability.

WHAT HAS THE GOVERNMENT SAID IT WILL DO?

Section 23 of the Representation of the People Act 1950 deals with the process of adding names to the electoral rolls, ie, your registration to vote in a particular constituency.

Before a local electoral registration officer adds a person’s name to the electoral rolls, they are supposed to check if they are entitled to be registered, and conduct a verification process.

The 2021 Amendment adds several sub-clauses to Section 23, which allow the electoral registration officer to ask a person registering to vote to provide their Aadhaar number to establish their identity

According to Union Law Minister Kiren Rijiju, this would be a voluntary process, not compulsory. Speaking to NDTV after the bill was passed, he said:

“It would be voluntary and not compulsory to link voter ID card with Aadhaar. Even if a citizen does not have an Aadhaar card, his name will not be deleted from electoral rolls. If you are above 18 and your name is in the voting list… then you are a voter.”

However, the wording of the 2021 amendment indicates otherwise. While it does say that the electoral register “may” ask for Aadhaar for registration and authentication, and even says that no applications to register to vote should be denied and that no entries should be deleted for failing to provide an Aadhaar number, it also says that a denial to furnish an Aadhaar number can only be due to a “sufficient cause as may be prescribed.”

This means that the Centre will be coming out with new Rules/Regulations which will specify under which conditions a person may be allowed to not give their Aadhaar number to an electoral registration officer. The process is therefore not going to be voluntary as the law minister claims.

WHY DOES INVOLVING AADHAAR IN THE PROCESS MAKE THIS DANGEROUS?

Section 22 of the Representation of People Act 1950 gives electoral registration officers the power to correct entries in the electoral rolls. This can be done if any entry is “erroneous or defective,” or a person has moved out of the particular constituency, or has died.

Before making any changes to the rolls, the electoral registration officer is supposed to give the person concerned a reasonable opportunity to be heard.

On that basis, you might wonder why bringing Aadhaar into the picture creates a problem. The problem is that with the involvement of Aadhaar, there are more opportunities for exclusion.

In 2015, a pilot National Electoral Roll Purification and Authentication Programme (NERPAP) was launched in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, to link Aadhaar numbers with voter IDs.

Even though the process was stayed by the Supreme Court after a few months, the seeding process had already been done for tens of lakhs of voters by then. When the electoral rolls for both states were published in 2018, there had been a huge number of deletions in both states: Nearly 30 lakh in Telangana, and over 21 lakh in Andhra Pradesh.

Chaos ensued at the 2018 Assembly polls in Telangana, with thousands of people finding out on the day that they had been removed from the rolls, without any prior notification (despite what Section 22 says). The problem was so bad that the Chief Electoral Officer for both states had to actually apologise for the problem.

RTI documents revealed that there hadn’t been any door-to-door verification used for the process when Aadhaar was linked to voter ID cards, just a de-duplication software.

There are a number of reasons why Aadhaar-linkage can lead to discrepancies in the electoral rolls.

On 27 March 2018, the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI), the government authority that runs the Aadhaar programme, had admitted in the Supreme Court that Aadhaar authentication for government services fails 12 percent of the time.

When it comes to linking to the electoral rolls, this would hopefully not be the level of error, because at least here there should be no requirement for biometric authentication – though it is as yet unclear what authentication requirements the rules brought in will have.

Even so, infrastructure failures can still lead to problems, whether because faulty net connections or site failures. If there is no follow-up verification process in person, this could mean a person being struck off the rolls for technical problems, rather than any actual problem with comparing Aadhaar with their voter ID.

On top of this is the fact that there is a great deal of inconsistency between names specified in different ID cards for many Indians, through no fault of their own.

Having a technology-driven process to verify these details (as was the method used by election officers along with the UIDAI in Telangana and in another brief attempt in Gujarat), would only raise the risk of exclusions.

In Jharkhand, for instance, a study found that 88 percent of ration cards deleted following a verification process introduced after Aadhaar linking, were actually genuine – but had still been deleted.

PROBLEMS WITH RECOURSE

Given electoral registration officers have always had the power to make changes to the electoral rolls, one might argue that even if there are exclusions, there is a way to get one’s name put back on the rolls.

However, bringing in Aadhaar adds another layer to make this more difficult. If the problem with authentication comes from the UIDAI, it becomes extremely difficult to redress as you would have to take your complaint to the UIDAI’s grievance redressal mechanism, not the local election officer.

This is fundamental danger to the right to vote, that an authority separate from the election commissions gets to have such a crucial say in it. This is not just about problems with authentication, but can potentially go even further.

This is because the UIDAI has the power to unilaterally deactivate a person’s Aadhaar number, without first giving them notice. Such persons are to subsequently be informed about the deactivation, following which they can take up the matter, again, with the UIDAI’s grievance redressal mechanism, which is basically just a contact centre (according to the UIDAI’s own Aadhaar (Enrolment and Update Regulations of 2016).

What all this means is that if there is a snafu with the linking of Aadhaar and your voter ID, or your voter ID gets suspended/deleted because of an Aadhaar issue, fixing the problem becomes extremely difficult.

Even if you do eventually manage to resolve the problem, this will take a great deal of time and effort, which means that if the issue crops up just before an election, you could find yourself having effectively lost your right to vote, no matter how long ago you registered, and how many times you have voted in the past.